What Is Money?

Money has always been a tool we use and take for granted that it works; our biggest concern generally boils down to finding ways to earn more money. While money takes on different shapes in our lives, it primarily exists in our bank accounts as digits on a screen or in our pockets as pieces of paper. Yet, despite our daily thoughts, interactions, and dependence on money to meet our needs, we rarely seem to question our personal understanding of money.

With the latest monetary innovations like bitcoin, “cryptocurrencies” and “non-fungible tokens” (NFTs) taking off amidst a global pandemic and a skyrocketing stock market, we hope to help you answer: What is Money?

Just like you control your shop, we want to empower you to control both your financial future and your path through today’s rapidly changing economic landscape. Because of this, we are launching a new series of posts on money, bitcoin, and cryptocurrency. In this article, the first of the series, we’ll examine the origins of money by describing the role of price in an economy. We’ll end with a definition of money that allows us to separate good money from bad money. These insights lay the foundation for the remainder of the series. You will then have a framework for properly analyzing the monetary quality of national currencies, bitcoin, and other alternative digital assets or cryptocurrencies.

Let’s go.

Barter Economies

To begin to understand money, we first need to understand prices.

A “price” is the agreed-upon quantity of commodity or Service A that is equal in value to quantity of commodity or Service B. For instance, if a barber agrees to cut a client’s hair in exchange for a chicken, then the price of that haircut is one chicken. Now say a tax advisor comes to the hairdresser and receives a haircut in exchange for one hour of tax preparation, then the price of a haircut is also one hour of tax preparation.

What you just read is a simple example of basic barter. “Market participants,” the people exchanging goods and services, agree on a price that makes both participants of the trade happy and commerce continues. This system of barter, however, has at least two issues: first, the hairdresser now is tracking the price of haircuts in multiple underlying commodities and services such as chickens or tax preparation services, and second, the hairdresser must want to own what the client has to offer also known as the “coincidence of wants” problem.

How did humans solve the issues of a barter economy? By inventing a new technology: money.

Good and Bad Money

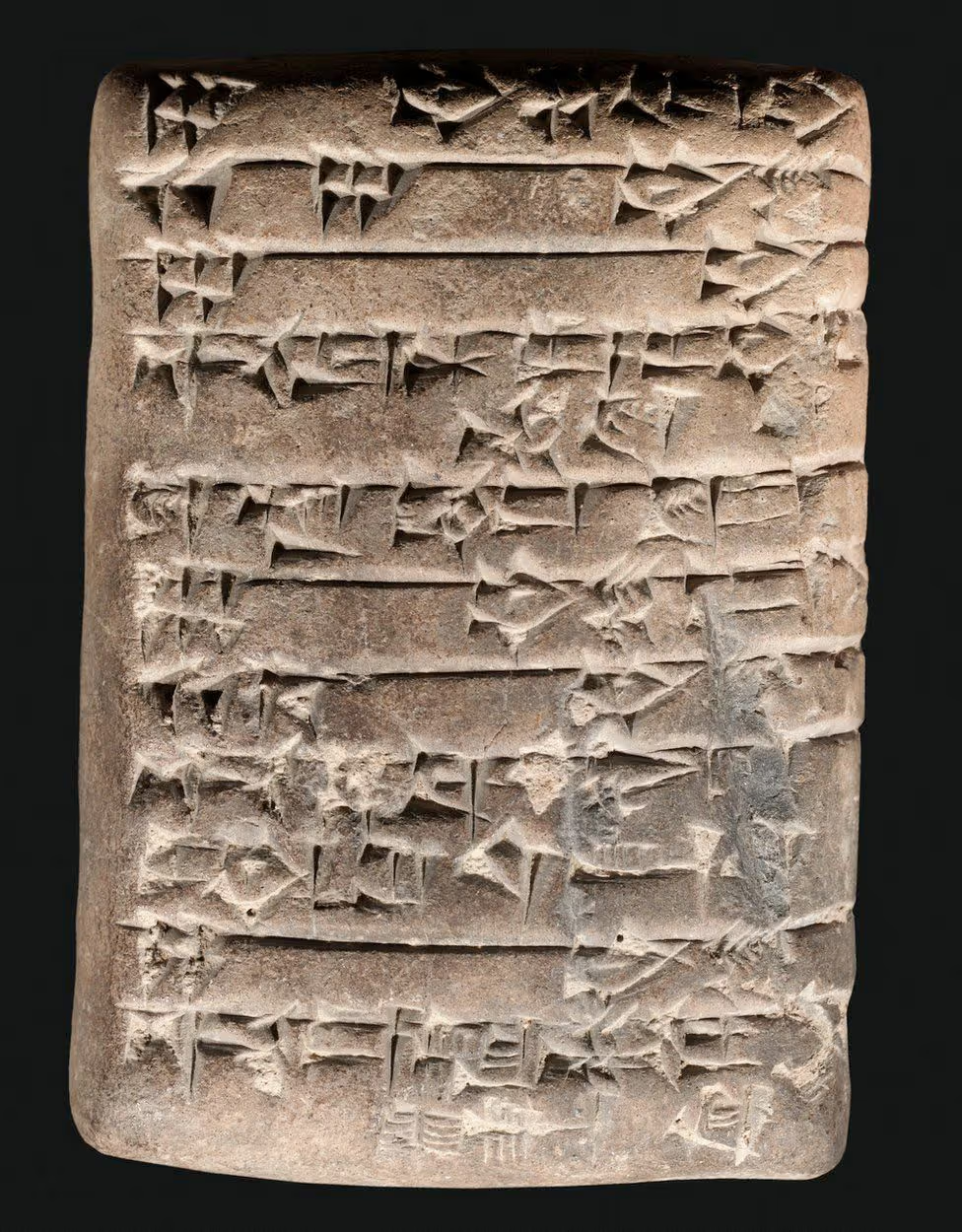

Money as a technology has existed for thousands of years. History tells us that needing to track debts and transactions caused the ancient Sumerians to inscribe symbols into clay tablets, ultimately giving rise to the first systems of writing and money.(2)

Because of this, we can determine that money is any commodity or anything that you can log into a ledger, a.k.a. a clay tablet, an online banking account, or a credit card that has "broad acceptance" in a culture. In a particular economic context, this is done in exchange for goods or services and repayments of private or public debts, for example, taxes. Interestingly, money arises spontaneously in any economy that requires trade.(3)

Money fulfills three primary functions for its users:

- Medium of Exchange - money is the third item or verified ledger entry accepted in a trade to avoid the need for direct barter.

- Unit of Account - money is used to denominate the value of accounts and assets by labeling each account or asset with the equivalent quantity of money for which these goods can be traded.

- Store of Value - money is a way to store economic value over time instead of directly consuming the value. For instance, we are paid hourly in money and not in apples because the apples would most likely go bad before we could trade them for something else we would instead consume, such as electricity at our homes.

While all money should serve these three functions, some forms of money objectively perform this task better than others. Money must be durable, portable, divisible, easily verified, and extremely difficult to reproduce or copy.

Gold, for example, has served as money for thousands of years because it does not degrade physically, must be mined from the ground to produce, and generally was considered portable and divisible enough to serve the needs of economic activity until the late 19th century.

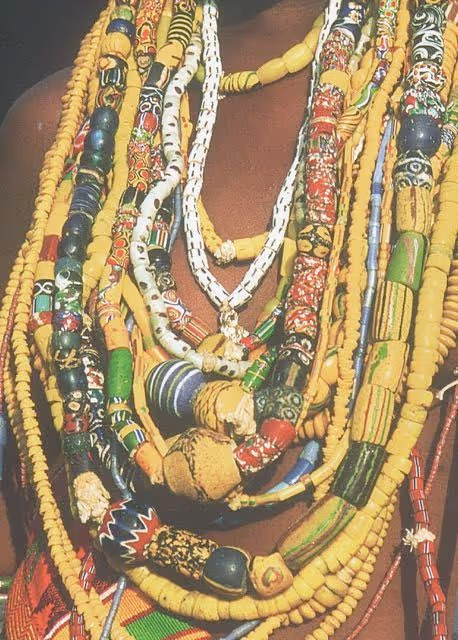

Durable Money

“Aggry beads” were an alternative to gold and precious metals used to facilitate trade amongst various kingdoms of West Africa.(4) People prized beads for their beauty and rarity. Yet, Portuguese traders arriving in the 15th century and later European settlers of the 16th and 17th centuries leveraged an asymmetry in glass production between Europe and Africa to silently debase local glass beads with cheaply produced beads from the European mainland. These beads were then traded directly for valuable, costly, physical goods, including slaves, to effectively rob the West African kingdoms willing to trade for these beads.

The beads were so prominent in the Transatlantic Slave Trade that they earned a new name: “slave beads.”(5)

Monetary debasement is a tragic consequence of power and information asymmetries and of using bad money. Ultimately, market participants in an economy force a Darwinian competition among various forms of money. It truly is the survival of the fittest when it comes to which forms of money present themselves as the best expression of durability, divisibility, verifiability, and resistance to debasement.(6)

Before You Go

Money is a revolutionary technology that has allowed us to move away from the traditional limitations of barter to a more free-flowing, interconnected economy. In essence, money as a technology grants each of us the power to store our labor as a single commodity that all participants in the economy desire. Money allows us to work today and consume tomorrow or ten years from now.

We also learned, however, that not all money is good. While all money should serve three primary functions (medium of exchange, unit of account, and store of value), some forms of money can perform these functions better than others. We measure how “good” or “sound” money is by observing its: durability, portability, divisibility, ability to be verified, and resistance to being copied (i.e., forgery or debasement).

Money is an empowering technology, yet economies that use worse forms of money than a competitor will ultimately lose out on real goods and services to disastrous consequences. Monetary asymmetries between the gold standard of Europe and the glass bead standard of many West African kingdoms fueled the Transatlantic Slave Trade, leading to a catastrophic transfer of wealth and cultural destruction.

In my next post, we will expand on these ideas and foundations of money to discuss how money ultimately evolves to meet the needs of its users. This long road of monetary evolution eventually collides with the digital and Internet revolutions and has produced some of the most incredible trends in money in human history.

_____________________________________________

- https://www.bbc.com/news/business-39870485

- https://www.archaeology.org/issues/213-1605/features/4326-cuneiform-the-world-s-oldest-writing

- https://cdn.mises.org/On%20the%20Origins%20of%20Money_5.pdf

- https://www.afrikapital.org/p/akori-beads-hyper-inflation-and-ancient

- http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/t/trade-beads/

- https://unchained.com/blog/bitcoin-obsoletes-all-other-money/

.avif)